Preparing low worm-risk paddocks

Preparing low worm-risk paddocks to prevent sheep from becoming heavily infected with worms is a key strategy in effective and profitable worm control.

The continuous recontamination of paddocks with worm eggs, that develop into larvae, is a major cause of ongoing worm problems for sheep. Grazing management can be an effective way to reduce the exposure of sheep to larvae on pasture and is especially important for vulnerable classes of sheep.

A recent ParaBoss webinar (plus 30-minute Q&A session) was held to help sheep and wool producers learn about using grazing management to minimise contamination of their pastures. Titled ‘Using pasture management for worm control’, the webinar was presented by the ParaBoss Extension Team’s Dr Fiona Macarthur, who has a long history of using grazing management for worm control. The webinar was recorded and is available free to view on the ParaBoss YouTube channel.

The webinar examined several possible grazing management strategies for worm control. Preparation of low worm-risk paddocks is one of them; others are year-round rotational grazing (which is not necessarily viable in all regions) and Smart Grazing for southern areas of Australia.

This Beyond the Bale article focusses specifically on the preparation of low worm-risk paddocks.

“The preparation of low worm-risk paddocks is a really important and a relatively easy tool for worm control,” Fiona said.

“Essentially, it involves, firstly, allowing time for most of the existing worm eggs and larvae on the pasture to die and, secondly, preventing more worm eggs from contaminating the pasture.

“As well as reducing the overall exposure of worms to the animals, it also reduces reliance on chemical drenches, which is important for slowing down the development of chemical resistance.

“It’s important to know the species of worm you have and what conditions support their survival and their die off. You can get a lab to do a larval differentiation which will identify the types of worms present and their proportion. This will help you know how to manage them.”

Which sheep are most susceptible to worms?

The gold standard is to have all sheep on low worm-risk paddocks. But that is not always feasible, so Fiona advises to try and ensure at least the most vulnerable stock – young sheep and pregnant and lactating ewes – are on paddocks that are as worm free as possible.

“Weaners should be your priority. They have never been exposed to worms and therefore haven’t had a chance to build up their natural immunity, so it’s important that the weaning paddock is a low worm-risk paddock,” she said.

“The next priority is your pregnant and lactating ewes. Their own resources are being used to grow their lambs rather than maintaining their own immunity, so lambing paddocks should be as free from worms as possible.

“Be mindful that your rams are also susceptible during times of high reproductive pressure. Dry ewes and wethers are generally more robust when it comes to worms.”

Allow time for most of the existing worm eggs and larvae to die

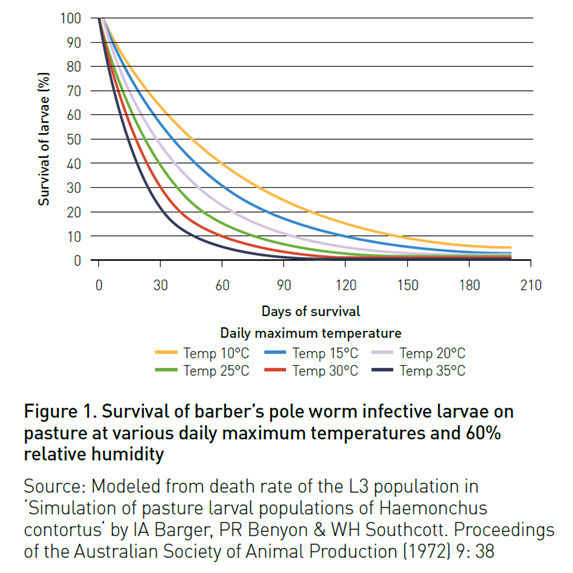

A very large proportion of the worm larvae on a paddock must die before being considered low worm-risk – this is generally about 95% from when a pasture is moderately to heavily contaminated. While an 85–90% reduction in larvae survival sounds substantial, it is not enough for this strategy to be effective, irrespective of the initial level of contamination.

“Preparing low risk paddocks is all about being proactive, not reactive. It involves forward planning,” Fiona said.

“In Australia, it can take up to six months for 95% of larvae to die, depending on your location and climatic conditions. This can sometimes be reduced to a two-month period in very hot, dry locations.”

Figure 1 shows the rate at which barber’s pole worm larvae die, but it is quite similar for scour worms. Choose the temperature line that fits your location in the few months prior to when the low worm-risk pasture is required and find where larval survival (left side of graph) drops to 5% to show the number of days required for 95% larvae to die.

The ParaBoss WormBoss Worm Control Program for your region will describe the times required in your region to prepare a paddock. Access it at tools.wormboss.com.au/sheep-goats/programs/sheep.php.

Prevent more worms from contaminating the pasture

While the larvae on the paddock are dying, further contamination must be prevented. The simplest and surest way to do this is to exclude sheep (and goats and alpacas) from the pasture during the preparation period so no new worm eggs can be deposited.

“Containment areas are a good option. You might already be using containment areas and not realise the worm control benefit you're getting,” Fiona said.

Simply spelling to let pasture regrow is a good option. However, leaving the paddock empty might not be affordable, nor the best use of the paddock. There are other ways to use the paddock during the preparation time without further contaminating the paddock with worm eggs.

Fiona says cattle can be grazed freely on the paddock.

“Grazing with cattle will utilise the feed and mop up any larvae that might be on the pasture as well. Sheep parasites are effective in sheep, goats and alpacas, so there isn’t any cross-contamination with cattle,” she said.

“Using the paddock for growing a crop, making hay or silage, or establishing new pasture are other great ways of utilising the paddocks and keeping worms out.”

You can graze the paddock with sheep (or goats or alpacas) under very specific conditions when they are not depositing worm eggs.

“You can graze for a short period of time with sheep following an effective short-acting drench and then remove the stock. Wethers are really useful for this because they have strong natural immunity,” Fiona said.

“But I would use caution here. First, know what an effective short acting drench is on your property by doing a faecal worm egg count reduction test (WECRT). It’s really important to find out what drenches are still working on your property and what level of resistance you have.”

If a long-acting drench is used, grazing can be longer (in line with the actual amount of persistence the product provides on your property). You should monitor worm egg counts (WEC) to identify what persistent length of protection you actually achieve.

“Grazing with sheep with a correctly used long-acting drench is definitely something that people utilise when they don't have any other option, when they can't keep sheep out of the paddock. But use the long-acting drench properly, which is with an effective priming drench, and then an effective tail cutter (exit) drench,” Fiona said.

For the sheep with the short-acting or long-acting drench, do regular WEC testing so you know if the sheep in the paddocks you're trying to clean up are carrying worms or not.

“For those in barber’s pole worm areas, Barbervax® is certainly a good tool to have in your toolbox; it lowers the larval pasture contamination by keeping the sheep at a lower infection level,” Fiona added.

“Longer term, and what definitely can't be underestimated, is selecting rams that have a low worm egg count ASBV.”

Monitoring low worm-risk pastures

Once you’ve prepared a low worm-risk paddock and moved your sheep in there, you should WEC test the sheep after 4–6 weeks to check their worm burden.

The WEC should be substantially lower than in the past (before using extra grazing management) or compared to a similar current mob that have not been grazing a low worm-risk paddock.

If the WEC results are not as good as expected, review your procedures. For example, was a mob of wormy sheep moved through this paddock on the way to the yards for drenching? It may also be that the starting level of worm larvae was very high and you will need longer to gain better control.

Woolgrowers are urged to use ParaBoss certified WEC providers to ensure they receive accurate WEC results.

More information:

- Recording of the webinar

- ParaBoss WormBoss Worm Control Program for your region

- Contact details of ParaBoss certified WEC providers and ParaBoss Certified Advisors

- WormBoss

Tap into best practice parasite management at www.paraboss.com.au

Collectively, the three Boss websites – WormBoss, LiceBoss and FlyBoss – promote best practice for the management of sheep parasites at the farm level, developed by a community of veterinary experts and parasitologists from across Australia and supported by the sheep industry.

This article appeared in the Autumn 2025 edition of AWI’s Beyond the Bale magazine that was published in March 2025. Reproduction of the article is encouraged.